What is Hypogonadism

Hypogonadism is low levels of sex hormones: oestrogen, progesterone, and testosterone.

Sex hormones are produced in the ovaries in females and the testes in males.

Hypogonadism happens when ovaries fail to produce female hormones, or the testes fail to produce male hormones.

If hypogonadism occurs at puberty, secondary sexual characteristics, such as pubic and arm hair, muscle development, breast development are affected.

A small amount of testosterone and oestrogen are also produced in the adrenal glands in both men and women. Fat cells store oestrogen.

How are sex hormones produced?

How are Sex Hormones produced?

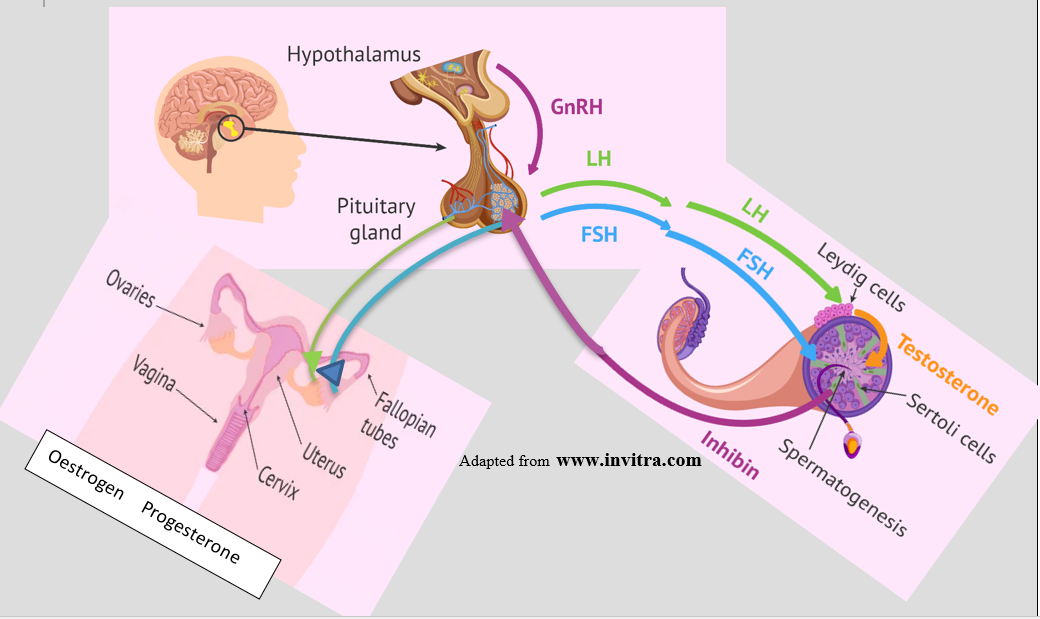

The hypothalamus secretes Gonadotrophic Releasing hormone (GnRH) that travels down the pituitary stalk to stimulate specialized cells in the pituitary to produce luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH).

LH and FSH act on the ovaries in women to produce oestrogen and progesterone and the testes in men to produce testosterone.

Hypogonadism can result from lack of stimulation from the hypothalamus (not enough GnRH), the pituitary (not enough LH or FSH) or if the gonadal organs (ovaries in females and testes in males) can’t produce enough hormone.

GnRH (hypothalamic)– LH-FSH (pituitary)- oestrogen, progesterone, testosterone gonadal) together are known as the hypothalamic-pituitary- gonadal (HPG) axis.

What is Female Hypogonadism?

What is Female Hypogonadism

The menstrual cycle is the result of cyclic production of GnRH, LH, FSH and sex hormones oestrogen and progesterone on average, every 28 days.

On day 1 of the menstrual cycle, FSH attaches to follicles (small egg sacs) in the ovaries. The follicles get larger and begin to mature eggs in preparation for ovulation. Follicles produce the steroid hormones estradiol (a form of estrogen). Estrogen levels continue to rise until around day 14 of the cycle. The rise in estrogen sends a signal to the hypothalamus to produce a surge of GnRH and, in turn, LH from the pituitary. This causes ovulation or the egg to be expelled from the follicle into the fallopian tubes. The empty follicle is called a corpus luteum, which produces progesterone to ready the uterine lining for a fertilized egg. If the egg is not fertilized the corpus luteum dies and levels of progesterone and estrogen fall, then levels remain low until the uterine lining is shed during menstrual bleeding. FSH begins the cycle over.

Female hypogonadism is the result of failure at any stage in the HPG axis. Central hypogonadism (pituitary) is most common in association with pituitary tumors.

How does Hypogonadism affect women?

How does hypogonadism affect women?

- Irregular or no menses (amenorrhea)

- Problems with Breast development, lactation, and breast feeding

- Vaginal dryness and thin lining

- Hypoactive sexual desire disorder

- Infertility

- Brittle bones & osteoporosis

- Increase in bad cholesterol and risk of heart disease

- Hot flashes and night sweats

- Sleep disturbance and fatigue

- Weight gain

- Post-menopausal uterine bleeding

- Increased facial hair growth (hirsutism)

- Higher risk of stroke

- Cognitive dysfunction

How is Hypogonadism in women diagnosed?

How is hypogonadism in women diagnosed?

A menstrual history is key, particularly if there has been an absence of menstrual cycles for 3 or more months or cycles are greater than 45 days apart.

Blood tests for LH, FSH, DHEAS and/or androstenedione level, testosterone, oestradiol, serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine (T4), prolactin, luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), estradiol (E2), and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) may be recommended in symptomatic patients to determine the source of the deficiency

A blood test at 8 AM for 17-hydroxyprogesterone level can be drawn if the clinician suspects late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH).

A progestin challenge may be done to induce withdrawal bleeding

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (with pituitary cuts and contrast) to determine the presence of a pituitary tumor.

A baseline bone mineral density is recommended.

A vaginal or abdominal ultrasound if polycystic ovarian syndrome or other anatomic changes are suspected.

Treatment for Female Hypogonadism

Treatment for female hypogonadism

Oestrogen replacement may be prescribed, together with progesterone for women who still have a uterus. Oral tables, transdermal patches, subcutaneous (under the skin), vaginal preparations and delivery devices can be used.

Taking oestrogen alone or oestrogen and progesterone is not recommended for the prevention of heart disease.

Side effects and risks of taking oestrogen and progesterone:

Mild: Breast tenderness, nausea, vomiting, bloating, stomach cramps, headaches, weight gain, darkening of the skin, hair loss, vaginal itching, abnormal uterine bleeding.

Serious: Blood clots, strokes and heart attacks, enlargement of uterine fibroids, and risk of cervical endometria and breast cancer.

It is important to talk with your medical team regarding risks and benefits that are specific for you.

Testosterone & DHEA. Current guidelines indicate there is not enough scientific evidence for testosterone replacement or treatment with DHEA in most women. A trial of 6 months of treatment may be indicated for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. This may cause increased facial and other unwanted hair growth.

Hirsutism: Guidelines recommend treatment with a combined estrogen–progestin oral contraceptive plus a trial of antiandrogen (testosterone lowering) medication after 6 months if further treatment is needed. Antiandrogen therapy alone is not recommended. Insulin-lowering drugs may also be indicated. For women who choose hair removal therapy, laser/photoepilation is suggested.

Dietary and psychological counseling may be useful.

In women desiring pregnancy further evaluation may be needed with a fertility expert and medication to stimulate ovulation.

What is Male Hypogonadism?

What is male hypogonadism?

In males, GnRH from the hypothalamus is released in pulses, usually during sleep. LH and FSH attach to the approximately 500 million Leydig cells in the testes to stimulate the production of testosterone. This process uses cholesterol, which is controlled by LH levels. High testosterone levels then stop the production of GnRH. This is called a feedback mechanism. Some testosterone is converted to oestrogen by a mechanism known as aromatization and may result in breast development (gynecomastia) in some men.

The clock and testosterone levels

During the day, Testosterone Levels are usually highest in the morning and peak in mid-afternoon. However, this pattern may be lost with aging.

Over a lifetime, testosterone levels are usually high at puberty but slowly decrease after middle age. Levels of oestrogen in men can increase with age, particularly in conjunction with weight gain or fat gain.

What are the effects of Testerone in Men?

What are the effects of testosterone in men?

Testosterone circulates in the blood bound to a specific protein. Blood levels are affected by LH levels but may also be affected by cortisol levels, thyroid levels, obesity, liver disease and the use of narcotic pain medications.

Testosterone acts by attaching to receptors on cells in multiple body tissues such as Sertoli cells in the testes to assist in the production of sperm. Receptors act like a lock and key to move the testosterone into the cells. Bone, muscle mass and strength, fat distribution and the production of red blood cells all require testosterone.

Signs and Symptoms of Low Hypogonadism in Men

What are the signs and symptoms of Low Hypogonadism in Men?

Testicles can shrink

Low interest in sex (low libido)

Sexual problems and inadequate erections, low sperm count and infertility

Brittle bones (osteoporosis)

Muscle weakness

Difficulty gaining muscle despite exercise

Fatigue and lack of energy

Body hair loss

Increased body fat, particularly midsection

Sleep disturbance

Low mood and depression

Difficulty with memory

Hot flashes

Diagnosis of Hypogonadism in Men

How is hypogonadism in men diagnosed?

A history of low libido, infertility, obesity, and diabetes are commonly found in men with hypogonadism.

Blood draw for LH, FSH and Testosterone levels should be measured several times before hypogonadism is diagnosed as levels fluctuate during the day.

MRI for pituitary tumour

Treatment of Hypogonadism in Men

Treatment of Hypogonadism in Men

Types of testosterone treatment:

Injections into muscle every 1-4 weeks (variable high and low levels).

Transdermal patches applied daily (may cause skin irritation).

Gels and creams applied to the skin (avoid direct body contact with partner, need to cover area until absorbed).

Buccal or under the tongue tablets in multiple daily doses. Absorb quickly.

Nasal gel applied to the nose up to three times day can cause congestion or irritation.

Pellets implanted under the skin and changed every 3-6 months. Require surgery.

Side effects:

Hair growth

Decreased sperm count

Acne

Gynecomastia (breast development)

Monitoring recommended during treatment

Red blood cell (RBC) count every 6 months. Testosterone may increase red blood cells, hematocrit and hemoglobin in blood, increased blood pressure and a risk of stroke.

Prostate specific antigen (PSA) and rectal exam yearly .

Bone density.

Sleep apnea evaluation.

* There is currently no evidence that therapy for hypogonadism increases the risk of heart disease or prostate cancer.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations

GnRH gonadotropin releasing hormone

LH luteinizing hormone

FSH follicle stimulating hormone

HPG hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

PSA prostate specific antigen

PCOS polycystic ovarian syndrome

References

References:

https://www.invitra.com/en/sex-hormones/

Barber TM, Kyrou I, Kaltsas G, Grossman AB, Randeva HS, Weickert MO. Mechanisms of Central Hypogonadism. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jul 30;22(15):8217. doi: 10.3390/ijms22158217. PMID: 34360982; PMCID: PMC8348115.

Ide V, Vanderschueren D, Antonio L. Treatment of Men with Central Hypogonadism: Alternatives for Testosterone Replacement Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Dec 22;22(1):21. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010021. PMID: 33375030; PMCID: PMC7792781.

Sharma A, Jayasena CN, Dhillo WS. Regulation of the

Hypothalamic-PituitaryTesticular Axis: Pathophysiology of Hypogonadism

Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am 51 (2022) 29–45

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2021.11.010 endo.theclinics.com

Olivius C, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Olsson DS, Johannsson G, Tivesten Å. Prevalence and treatment of central hypogonadism and hypoandrogenism in women with hypopituitarism. Pituitary. 2018 Oct;21(5):445-453. doi: 10.1007/s11102-018-0895-1. PMID: 29789996.

Wheeler KM, Sharma D, Kavoussi PK, Smith RP, Costabile R. Clomiphene Citrate for the Treatment of Hypogonadism. Sex Med Rev. 2019 Apr;7(2):272-276. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.10.001. Epub 2018 Dec 3. PMID: 30522888.

Misra M. Effects of hypogonadism on bone metabolism in female adolescents and young adults. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012 Jan 24;8(7):395-404. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.238. PMID: 22271187.

Fleseriu M, Hashim IA, Karavitaki N, Melmed S, Murad MH, Salvatori R, Samuels MH (2016) Hormonal replacement in hypopituitarism in adults: an endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101(11):3888–3921. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-2118

Miller KK, Biller BM, Schaub A, Pulaski-Liebert K, Bradwin G,

Rifai N, Klibanski A (2007) Effects of testosterone therapy on

cardiovascular risk markers in androgen-deficient women with

hypopituitarism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92(7):2474–2479. https

://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-0195

Wierman ME, Arlt W, Basson R, Davis SR, Miller KK, Murad MH, Rosner W, Santoro N. Androgen Therapy in Women: A Reappraisal: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 99, Issue 10, 1 October 2014, Pages 3489–3510, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-2260

Martin KA, Anderson RR, Chang RJ, Ehrmann DA, Lobo RA, Murad MH, Pugeat MM, RL, Evaluation and Treatment of Hirsutism in Premenopausal Women: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 103, Issue 4, April 2018, Pages 1233–1257, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-00241

Author:

Chris Yedinak DNP,FNP.

Associate Professor

Oregon Health & Sciences University Portland. OR. USA

Updated: November 2022